You Don’t Have to Look Like a Fell Runner

How Khan quietly changed what’s possible on the fells

Dispatches from the edges of endurance, mischief, and moving well together.

On Friday evening, 25 April 2025, at 6:30 p.m., brother Khan, one of our own, set out to run the Bob Graham Round (BGR).

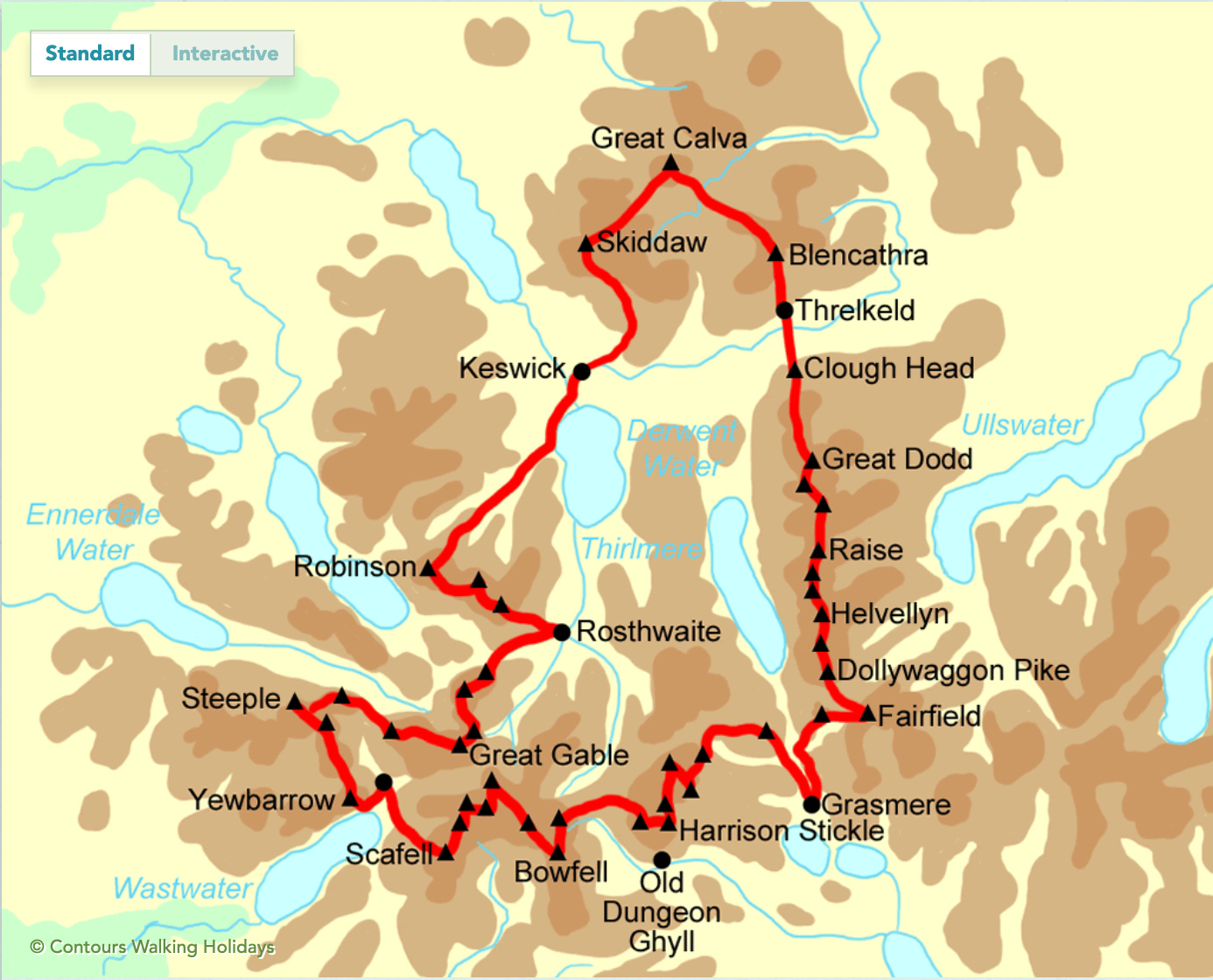

The Bob Graham Round (The BOB)

If you’ve never heard of The Bob Graham, here’s the low-down: it’s a 66-mile circuit in the Lake District, covering 42 of its tallest fells, with over 8,000 metres of elevation gain.

To be counted as an official “Round,” it has to be completed in under 24 hours.

Paving the Way

Khan isn’t the first guy in our team to take on this UK mountain test-piece (indeed, we’ve got a Double Bob attempt happening this June; watch this space!), but one glaring detail sets this attempt apart from all who have gone before him…the dude is sixteen and a half stone!! 105.5kg 232.5 lbs / 16 st 7 lbs

Big Dudes

16 st 7 lbs is 105.5kg in new money (232.5 lbs for our American friends).

We wouldn’t be Poles & Crocs if we didn’t relentlessly take the piss out of each other so here’s other things that are the equivalent of Khan’s bodyweight…

A Baby Rhino

A Sumo Wrestler

A Spinet Piano

The Man Himself

Racing Snake

People who aren’t built like sumo wrestlers.

It’s no coincidence that fell-runners in the UK are called ‘Racing Snakes’. Tall and slender is not just an aesthetic; it’s a key component in keeping the brain at a safe temperature; lighter runners produce and store less heat at the same running speed; hence, they can run faster or further before reaching a limiting rectal temperature.

When you think of fell runners, you probably think tall, long-limbed, gazelle-like creatures. Unfortunately, I can’t find any anthropometric profiles of the current Bob record holder, American ultrarunner Jack Kuenzle (finish time of 12 hours and 23 minutes), but he sure does look the part of a tall and lean fell runner.

Body Mass Index

Khan’s BMI is just shy of 30. For comparison, the entire six-nations forwards cohort in 2022, 61 out of 94 players had a BMI >30.

The average BMI for the entire Kerry Gaelic football team in 2019 was 24.7.

Rafal Nadal and Roger Federer have recorded BMIs of 24.8.

The Liverpool FC team (2022) has, average BMI was 23.1.

To beat this BMI thing to death… to be eligible to join the Royal Navy, a Body Mass Index (BMI) between 18 and 28 is generally required.

So Khan would be ineligible to join either the Royal Navy or Liverpool FC. I’ll have to ask him how he feels about that…but what about being a runner?

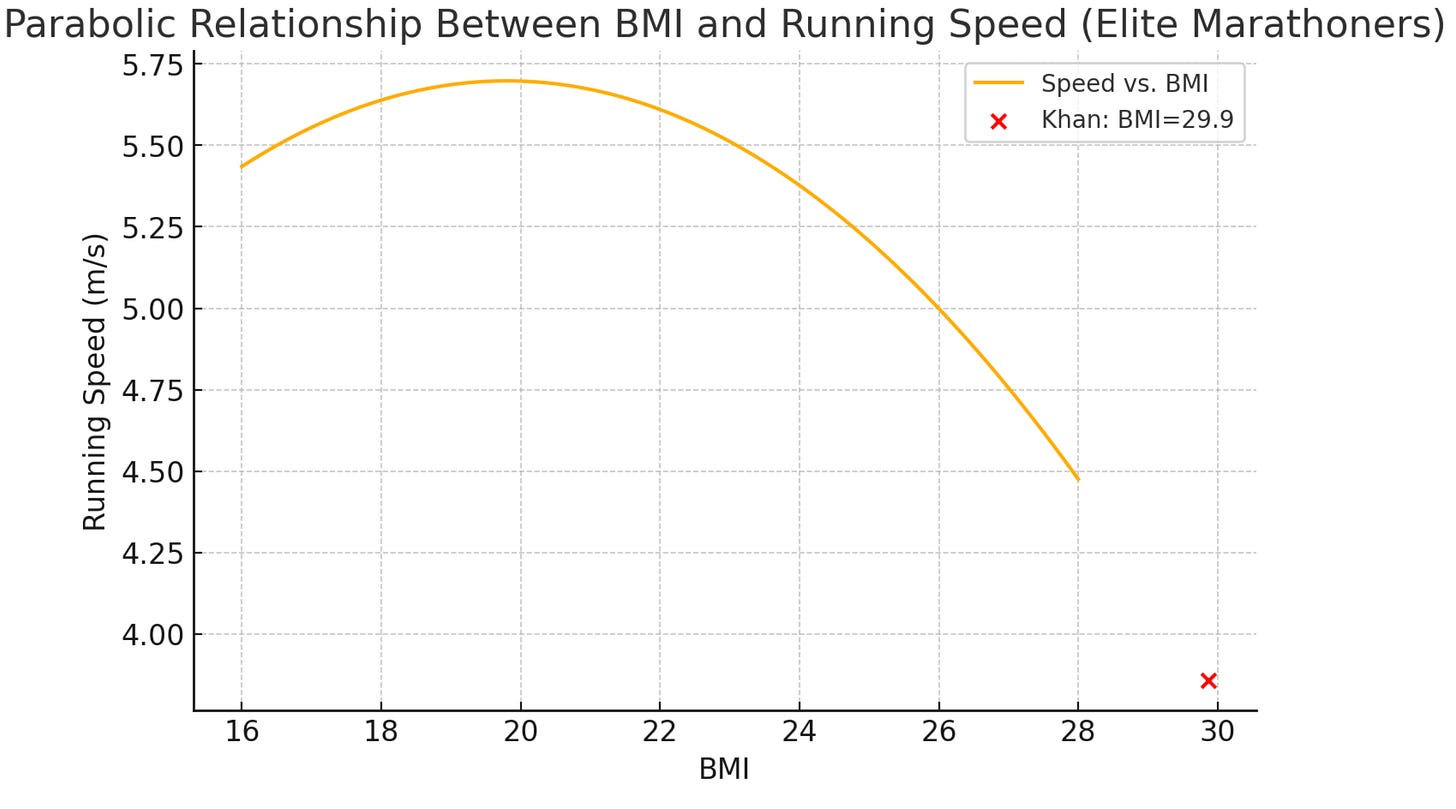

In one scientific paper, 100 elite marathon runners were assessed, and the ideal BMI was found to be around the 20 mark.

As you can see, running speed rapidly drops off as BMI increases. Whilst Khan’s little red cross has swan-dived off the end of the chart!

Khan stepped off on the day of his attempt weighing nothing shy of 105.5kg (232.5 lbs / 16 st 7 lbs).

In fell running terms, that is very unusual—and may even be unique.

We’d love to hear from anyone with any information regarding runners over 100kg completing or even attempting the Bob. If that’s you, please shoot us a message!

Power to Weight Ratio

Most who attempt The Bob are lean, whippet-like fell runners who’ve spent years getting to know the terrain and tuning their bodies for the job. It’s more mountain pilgrimage than race—quiet, punishing, and deeply British.

Most people know that BMI is a pretty rudimentary formula, and in athletic populations, the number becomes fairly meaningless, to put it politely. A 6ft 2”, 100kg bloke at 10% body fat isn’t the same animal as a 6ft 2”, 100kg bloke at 25% body fat.

Power-to-Weight: The Engine Behind the Mass

Khan’s story isn’t just about being heavy. It’s about being heavy and powerful, which is a very different thing.

At 105.5kg (232.5 lbs / 16 st 7 lbs), the margins are brutal. When you’re moving that kind of mass over mountain terrain for 24 hours, it only works if you’ve got the engine to back it up. That’s where power-to-weight ratio comes in.

Even at ultra distances, power is what propels the body forward. Sure, efficiency and economy matter, but if you’re carrying extra kilos, you need the force to keep driving them forward, hour after hour. It’s physics. Mass multiplied by acceleration.

Put simply: the more you weigh, the more power you need to generate just to keep pace. And Khan? He’s built a serious engine.

*Here’s what a typical heavy gym session might look like for him:

115kg × 2 Hang Clean

3 Super Sets of 167.5kg × 1 and 125kg × 5 (moved at athletic speed)

205kg Deadlift for a moderate triple

These aren’t “ultra-runner” numbers. They’re elite strength-endurance numbers. They point to years of smart, consistent training focused not on aesthetics, but on function. He’s trained not just to endure, but to endure with power.

That’s the bit most people miss when they see someone bigger moving fast over long distances. It’s not just guts. It’s not even just grit. Its strength, converted into repeatable power, sustained over time.

Khan didn’t get around despite his weight. He got round because he’d built the capacity to move it, hour after hour, summit after summit.

*working for over a decade with undoubtedly one of the UK’s best strength and athletic coaches. Who happens to be one of our own, but that’ll have to be an article on its own.

Defying the Odds

This isn’t a story about defying odds in the usual headline sense. Khan didn’t shout his way around the fells or try to prove a point. What he did was far more grounded—and far more useful. He observed. He experimented. He took the kind of notes that help others try something they might otherwise have written off as “not for people like me.”

If you’ve ever looked at long, mountainous endurance events and thought, “That would break me”, Khan is here to tell you that, with a little bit of planning and a ruthless eye for leaving no stone unturned in your preparation, you could be thinking “this is totally for me!”.

We’d invite you to think about the possibility of pulling off the outrageous. Especially if you carry more weight than most runners and wonder if your body could handle it.

The Nicky Spinks Method

Speaking about his preparation and mindset, Khan refers several times to the “Nicky Spinks method”—a practical approach borrowed from one of the most respected names in British fell running. Nicky Spinks is known not just for her extraordinary endurance feats, but for her calm, clear-thinking mindset. One of her guiding principles: “If you’ve thought about it three times, you’ve already thought about it ten. Just do it.” That kind of clarity proved essential for Khan.

Success Doesn’t Mean You’ve Finished

Ever the generous soul, Khan wasn’t finished when he successfully stepped over that finish line: 23hrs 18mins. Almost immediately, Khan took himself to one side to craft his observations with the sole aim of helping others achieve the same. When most would be thinking of a hot bath and a beer…possibly not in that order. Khan was thinking, “How could I pay this moment forward?”

And if that’s not the definition of selflessness, I don’t know what is.

Here are Khan’s reflections, shared with us in the hope they’ll support someone else:

Observations from the runner

(From a bigger guy’s perspective)

- Putting the poles in poles and crocs…Heavier guys are more reliant on poles to save the legs. This causes problems with hand blisters and cramping triceps—something to watch out for.

- Cramp and salt sticks. I’ve never really suffered from cramp in ultras before, but I did on the BGR. Make sure salt sticks are more readily available from Leg 3 onwards.

- The Nicky Spinks method: If you’ve thought it three times, then you’ve thought it ten times. Just stop and do it.

- Footwear. Invest time in deciding and trialling it. Apply the Nicky Spinks method to any changes. For me, Thundercross for Legs 1 and 2, then Mafate Speeds for the rest.

- Temp regulation. Be disciplined with it. Buff, hat, gloves, jacket—put them on and off as many times as needed (Nicky Spinks again).

- Marginal Gains. Keep it light, bouncy, fun on the feet. Manage effort—keeping an easy pace for Legs 1 and 2 will set you up for the rest. Always focus on running technique, applying Leon/Venus videos about hip and foot positioning. According to Garmin I did 140,000 steps—so even if better technique gained me 1cm per step, that’s close to a mile over the course. And that doesn’t even factor in the energy saving.

- Nausea. Midway through Leg 3 I got hit with nausea—sloshing in my stomach even off water. Two things helped: consume while going uphill so there’s a window of less turbulence, and—do a shit.

- Mental game. Trust your body can do it. Just tell it to keep moving.

- Checkpoints are not for resting. You gain nothing but seizure. They are for admin—you don’t need more than six minutes, if that.

- Support runner safety net. Make sure on each leg you have someone so rapid and robust that they could carry you on their own if everyone else falls off.

- Four points of contact is a see-off. Take the slightly longer, less degrading route.

- Mules. Know the power of just your friendly face presence close by, even in silence. Don’t shoot ahead—it is an absolute mind-fuck for the runner.

- Leg 4 should be done in the light—but my God, buckle up. My internal monologue that kept my feet moving bounced between, *“It won’t be as bad as it looks, it won’t be as bad as it looks,”* and visualising my 18-month-old observing me.

- Knowing the ground (the terrain you’re going to cover) is a big mental boost.

There’s a humility in the way Khan shares his experience. No inflated sense of achievement. No drama. Just a man who set his mind to something most people would never even consider, especially at his size, and followed it through.

This isn’t about shattering records or making headlines. It’s about expanding the definition of what’s possible. About stepping outside what people think a “runner” looks like. About facing down that voice that says, Not me, and replying: Why not?

If you’re a bigger runner, or just someone who’s counted themselves out of endurance challenges because of how they’re built, this story is a quiet invitation:

You belong on the fells too.

Who is Nicky Spinks?

Nicky Spinks is one of the most iconic endurance runners in British fell running history. A farmer by trade and a late starter in the sport, she became known for her toughness, precision, and humility. Among her many achievements, she completed the Bob Graham Round in under 18 hours, held the women’s record for the Paddy Buckley and Ramsay Rounds, and was the first person to complete doubles of all three UK rounds (BGR, PBR, Ramsay)—each twice over, within 48 hours. She also did all this while living with and recovering from cancer. Her approach blends fierce attention to detail with a calm, unshowy resolve—qualities many runners, including Khan, have drawn on when preparing for their own challenges.

Annexe: The Nicky Spinks Method

A practical approach for long days in the hills

The “Nicky Spinks method” isn’t just a line—it’s a mindset. At its core is a simple truth: act early, act honestly, and don’t let small discomforts become big problems.

Here are its foundations:

Decisive self-awareness

Spinks advocates listening closely to your body and acting quickly. If something’s niggling—whether it’s a rubbing sock, the need for a layer change, or a drop in energy—don’t wait until it becomes a problem. Make the change now.Constant micro-adjustments

Keep tweaking. Layers on and off, food in small amounts, poles adjusted, laces re-tied. These small actions prevent big problems later and help you stay in rhythm.Practical discipline

Stay efficient. Don’t waste time at checkpoints or indulge distractions. Have a plan, but be ready to adapt. Spinks is known for running with military precision, but never at the cost of responsiveness.Emotional steadiness

There’s no glory in unnecessary suffering. Spinks’ approach is rooted in reducing friction—physically and mentally—so you can keep moving forward with as little drama as possible. Sometimes that means taking an unusual line or pausing to deal with something minor before it derails your round.

It’s a method that has quietly shaped many successful rounds, including Khan’s.

Poles & Crocs is a collective of runners, coaches, and curious bodies drawn to the edges of endurance and expression. We’re here for mastery over medals—for the deep satisfaction of getting good at something, whether or not the world is watching.

You can find more or share your story at polesandcrocs.substack.com